History

Captain John Smith, one of the original tourists to the area, visited Essex during the winter of 1607-08, when he wrote of the “excellent, pleasant, fertile, and goodly navigable” Rappahannock Valley. On his first visit he did not linger. While he was trying to disembark near what is now the county seat of Tappahannock, the Native Americans drove him back to his ship. Rest assured, present day visitors will not meet with this hostile welcome! Using the river as their highway, people and goods moved along its shores

In 1645 Bartholomew Hoskins patented the Tappahannock site, which became known, at various times as Hobbs His Hole, Hobb’s Hole, the short-lived New Plymouth, and the Indian name Tappahannock. The port town was to become a center of commerce during the 17th and 18th centuries establishing a crossroads.

During Bacon’s Rebellion in 1676, armed men gathered near Piscataway Creek and defeated Governor Berkeley’s cavalrymen. Later they prevailed in the Dragon Run Swamp, but eventually English warships and troops suppressed the uprising. Frontier patrols, however, were maintained against hostile northern Indians into the early 1700’s.

In 1692, the now extinct Rappahannock County split into Essex and Richmond Counties. Still heavily influenced by British domain, the county name of Essex may have come either from the shire or county in England, or as a nod to the Duke of Essex himself (patrons are often generous!). Essex County Virginia today still maintains links with Essex County Council and the people of Chelmsford, Essex, England.

An early name for the area that would become known as Tappahannock was Hobbs His Hole, named for ship captain Richard Hobbs. The Hobbs family had land in Poulton, Hampshire, England. Richard Hobbs left England sometime around 1656, and by 1665 he had come into possession of an 800 acre tract of land on the south side of the Rappahannock River that included a small creek. The mouth of the creek became known as Hobbs’ His Hole Harbor, hole in this instance meaning a spot of deeper water where a ship could safely drop anchor. The town that sprang up was comprised of 50 acres divided into half acre squares. Tappahannock’s first call to duty was as a port for river traffic. Colonial Charm is evident in a number of private homes still in existence, as well as in numerous businesses still existing in the buildings of that era. Street names such as Marsh, Queen, Prince, Duke, Cross, Church, and Water are original nomenclature. In 1705, the town was once again known by its Indian name of Tappahannock meaning “town on the rise and fall of water.”

With the building of the first Downing Bridge to the Northern Neck in 1927, reliance on the river started to change. Until then, the only way to cross the Rappahannock was by ferry from either Tappahannock or Ware’s Wharf. The present bridge was built in 1963.

Use the + and – icons to expand and close each History section.

Captain John Smith, one of the original tourists to the area, visited Essex during the winter of 1607-08, when he wrote of the “excellent, pleasant, fertile, and goodly navigable” Rappahannock Valley. On his first visit he did not linger. While he was trying to disembark near what is now the county seat of Tappahannock, the Native Americans drove him back to his ship. Rest assured, present day visitors will not meet with this hostile welcome! Using the river as their highway, people and goods moved along its shores

In 1645 Bartholomew Hoskins patented the Tappahannock site, which became known, at various times as Hobbs His Hole, Hobb’s Hole, the short-lived New Plymouth, and the Indian name Tappahannock. The port town was to become a center of commerce during the 17th and 18th centuries establishing a crossroads.

During Bacon’s Rebellion in 1676, armed men gathered near Piscataway Creek and defeated Governor Berkeley’s cavalrymen. Later they prevailed in the Dragon Run Swamp, but eventually English warships and troops suppressed the uprising. Frontier patrols, however, were maintained against hostile northern Indians into the early 1700’s.

In 1692, the now extinct Rappahannock County split into Essex and Richmond Counties. Still heavily influenced by British domain, the county name of Essex may have come either from the shire or county in England, or as a nod to the Duke of Essex himself (patrons are often generous!). Essex County Virginia today still maintains links with Essex County Council and the people of Chelmsford, Essex, England.

An early name for the area that would become known as Tappahannock was Hobbs His Hole, named for ship captain Richard Hobbs. The Hobbs family had land in Poulton, Hampshire, England. Richard Hobbs left England sometime around 1656, and by 1665 he had come into possession of an 800 acre tract of land on the south side of the Rappahannock River that included a small creek. The mouth of the creek became known as Hobbs’ His Hole Harbor, hole in this instance meaning a spot of deeper water where a ship could safely drop anchor. The town that sprang up on that site was comprised of 50 acres divided into half acre squares. Tappahannock’s first call to duty was as a port for river traffic. Colonial Charm is evident in a number of private homes still in existence, as well as in numerous businesses still existing in the buildings of that era. Street names such as Marsh, Queen, Prince, Duke, Cross, Church, and Water are original nomenclature. In 1705, the town was once again known by its Indian name of Tappahannock meaning “town on the rise and fall of water.”

With the building of the first Downing Bridge to the Northern Neck in 1927, reliance on the river started to change. Until then, the only way to cross the Rappahannock was by ferry from either Tappahannock or Ware’s Wharf. The present bridge was built in 1963.

Use the + and – icons to expand and close each History section.

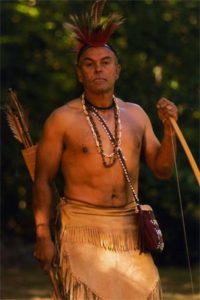

Pre 1608 The Rappahannock Tribe

The Rappahannock probably first encountered the English in 1603. It was likely Captain Samuel Mace who sailed up the Rappahannock and was befriended by the Rappahannock chief. The record tells us that the ship’s captain killed the chief and took a group of Rappahannock men back to England. In December 1603, those men were documented giving dugout demonstrations on the Thames River. In December 1607, the Rappahannock people first met Captain John Smith at their capital town ‘Topahanocke”, on the banks of the river bearing their name. At the time, Smith was a prisoner of Powhatan’s war chief, Opechancanough. He took Smith to the Rappahannock town for the people to determine whether Smith was the Englishman who, four years earlier, had murdered their chief and kidnapped some of their people. Smith was found innocent of these crimes, at least, and he returned to the Rappahannock homeland in the summer of 1608, when he mapped 14 Rappahannock towns on the north side of the river. The territory on the south side of the river was the primary Rappahannock hunting ground.

English settlement in the Rappahannock River valley began illegally in the 1640s. After Bacon’s Rebellion, the Rappahannock consolidated into one village, and in November 1682 the Virginia Council laid out 3,474 acres for the Rappahannock in Indian Neck, where their descendants live today. One year later, the Virginia colony forcibly removed the tribal members from their homes and relocated them, to be used as a human shield to protect white Virginians from the Iroquois of New York, who continued to attack the Virginia frontier and to threaten the expansion of English settlement.

In an effort to solidify their tribal government in order to fight for their state recognition, the Rappahannock incorporated in 1921. The tribe was officially recognized as one of the historic tribes of the Commonwealth of Virginia by an act of the General Assembly on March 25, 1983. In 1996 the Rappahannock reactivated work on federal acknowledgement, which had begun in 1921, when Chief George Nelson petitioned the U.S. Congress to recognize the Rappahannock civil and sovereign rights. In 1995 they began construction of their cultural center project and completed two phases by 1997. In 1998 the Rappahannock tribe elected the first woman chief, G. Anne Richardson, to lead a tribe in Virginia since the 1700s. As a fourth-generation chief in her family, she brings to the position a long legacy of traditional leadership and service among her people. Also in 1998, the tribe purchased 119 acres and established a land trust on which to build their housing development. They build their first home and sold it in 2001.

The Rappahannock Tribe hosts their traditional Harvest Festival and Pow-wow annually on the second Saturday in October at their Cultural Center in Indian Neck. They have a traditional dance group called the Rappahannock Native American Dancers and a drum group called the Maskapow Drum Group, which means “Little Beaver” in the Powhatan language. Both of these groups perform locally and abroad in their efforts to educate the public about Rappahannock history and tradition.

Sources: 1. The Virginia Indian Heritage Trail. Edited by Karenne Wood. A Project of the Virginia Council of Indians. In partnership with the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities. (2007) – Reproduced by kind permission of the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities.

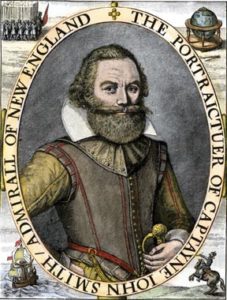

1608: Essex and John Smith

John Smith, the adventurous leader of the early Jamestown settlers, visited the lands of modern Essex County three times between 1607-1608. On the first occasion he was a prisoner, the second time an explorer and finally a mediator. He thought well of the area writing, “It is an excellent, pleasant, well inhabited, fertill, and goodly navigable river”.

Smith’s first visit to Essex County occurred when he was captured along the Chickahominy River in the winter of 1607-1608. He was exhibited throughout villages of the Powhatan Indians, then, as Smith wrote, “From hence this kind King conducted mee to a place called Topahanocke, a kingdom upon another River northward”. Smith was delivered to this village of the Rappahannocks on Christmas Day 1607 because of crimes he was suspected of committing a few years earlier. Upon seeing him, however, they judged him not to be the perpetrator.

Smith’s second visit was in the summer of 1608 while on an exploration trip up the Rappahannock River with 14 soldiers and their Wighcomoco guide Mosko. Smith’s small party encountered a small group of Rappahannocks on shore, possibly near the mouth of Piscataway Creek. Before commencing trade, each side traded a hostage with Anas Todkill going ashore. Once ashore, Todkill “perceived two or three hundred men as he thought behind the trees”. Todkill yelled a warning, and a brief and furious exchange of arrows and gunshots followed. Many Rappahannocks were killed and a wounded Todkill was recovered. The Rappahannocks continued attacks as the sailing vessel ventured further upriver.

On the party’s trip back down the river, Smith issued a strong warning to the Rappahannocks, “he would now burne all their houses, destroy their corne, and forver hold them his enemies”. The Rappahannocks feared the new weapons of the English and ceased their attacks. On his final visit to Essex, Smith helped broker a peace treaty between the Rappahannocks and the Moraughtacund tribe. After Smith’s visits, there would be little English activity in Essex until the 1640s.

Sources:

1. Settlers, Southerners and Americans: The History of Essex County, Va.. by James B. Slaughter. Walsworth Publishing Co., Inc., 1985. (available at the Essex County Museum and Historical Society)

2. Essex County Historical Society Bulletin, Volume 49. A Brief and True Account of the Writings of Captain John Smith and the Beginnings of American Literature, by Robert Alexander Armour. September 2007

3. The Complete Works of Captain John Smith, Vol. 2. Edited by Phillip L. Barbour

4. The Jamestown Narratives. Edited by Edward Wright Haile. RoundHouse Books, 1998. (available at the Essex County Museum and Historical Society)

1645: First Land Grants

By 1645, English settlers had battled winter, starvation, disease and the native tribes to slowly move up the coastline from Jamestown. They had learned there would be no gold or quick fortunes in the New World. Prospering or even surviving would require years of hard work. Growing and selling the tobacco plant to Europe became the source of wealth and medium of exchange. Many would become wealthy and begin the traditions of hospitality and generosity for which Virginia would became famous. Many others would soon come seeking a new life. The roughly 14,000 settlers in Virginia at this time always needed new, fertile land to grow tobacco. The hardiest souls looked to the frontier including the “Topahanoke” area. Bartholomew Hoskins was the first European to patent land in the area that latter becomes Tappahannock. Hoskins Creek bears his name.

Civil War in England during this era caused a flood of new settlers to America. The expanding population created the new counties of Northumberland in 1645, Westmoreland in 1653, Lancaster in 1651 and old Rappahannock County in 1656. By that time, Virginia’s population had grown to almost 25,000 but only about 200 resided in the “Topahanoke” area of Rappahannock County. Some of the earliest settlers included John Catlett, Thomas Lucas and Toby Smith.

About this time, planters changed from relying on indentured servants to using enslaved Africans. With slave labor, many Europeans built huge plantations, amassed fortunes and became the most powerful families in Virginia. The combination of tobacco, slavery, plantation life and family legacies became a way of life that lasted for more than 200 years.

Sources:

1. Settlers, Southerners and Americans: The History of Essex County, Va.. 1985, by James B. Slaughter (available at the Essex County Museum and Historical Society)

1682: Establishment of Tappahannock

Virginia’s expanding population reached around 40,000 in the 1670s. A stratified society had emerged with an established aristocracy, former indentured servants, slaves and native tribes on the frontiers.

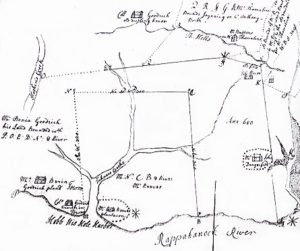

Tensions boiled over in 1676 in what would later be called Bacon’s Rebellion. Nathaniel Bacon led disgruntled, smaller planters in a vigorous war against local tribes in defiance of Governor Berkeley. Around the former Rappahannock village of “Topahanocke”, Thomas Goodrich and his son Benjamin were supporters of Bacon. The war spread to attacks on Berkeley’s supporter and the Governor fled. Royal troops and ships soon arrived to crush the rebellion.

Retribution by Governor Berkeley was harsh for some, but the House of Burgesses did take measures to address the rebellion’s causes. The total reliance on a single cash crop was recognized as a critical problem. Diversification of Virginia’s economy and social structure by the creation of towns was considered the solution.

In 1680, Virginia law required each county to create a town. In old Rappahannock County, 50 acres was purchased from Benjamin Goodrich for 10,000 pounds of tobacco to create the town of Tappahannock on March 25, 1682. A small village named Hobbs His Hole already existed, but the chartered name was New Plymouth. In 1705 the name was changed to Tappahannock. In 1706, Harry Beverley mapped out the town lots and street names that are still in use today. The name Hobbs Hole persists even now, but town growth was slow to come.

Sources:

1. Settlers, Southerners and Americans: The History of Essex County, Va.. 1985, by James B. Slaughter (available at the Essex County Museum and Historical Society)

2. Essex County Historical Society Bulletin. The Establishment of Tappahannock with Sketches on it Founders: Bartholomew Hoskins, Thomas and Benjamin Goodrich, Thomas Gouldman & Harry Beverley. November 1971

a: Historic Homes, 2002. by Anita and Gordon Harrower and Robert LaFollette (available at the Essex County Museum and Historical Society)

1692: Essex County Established

Three primary factors drove the creation of most new counties in Virginia’s early colonial period: increasing population, new land for tobacco fields and the difficulty of travel.

At the time of Bartholomew Hoskins patent (1645), the area around “Topahanocke” was part of York County. Virginia’s population nearly doubled in the 1650s with much of the growth along the shores of the Rappahannock River. This led to the creation of Northumberland (1645), Westmoreland (1653), and Lancaster (1651).

The “Topahanocke” area was then part of Lancaster County. The 1651 will of Epaphroditas Lawson, who lived south of the Hoskins patent, is on file in the Lancaster Courthouse and is one of the oldest wills in the country. The growing population created old Rappahannock County (1656), encompassing the current lands of Essex and Richmond counties on both sides of the river.

Travel in 17th century Virginia made court business a difficult affair, so another division occurred. On April 16, 1692 Rappahannock County was divided into Essex County on the south side of the river and Richmond County on the north side of the river. Court records from Rappahannock County were moved to Essex where they reside today. Richmond County was compensated for its citizen’s contributions to the purchase of land for Tappahannock.

Thus, the lands we now call Essex have gone through the following transformations:

| – Charles River County (1634) – York County (1643) – Lancaster County (1651) – Old Rappahannock County (1656) – Essex County (1692) – Creation of Spotsylvania County in 1721 removed northwestern land – creation of Caroline County in 1728 removed northwestern land |

Sources:

1. Settlers, Southerners and Americans: The History of Essex County, Va.. 1985. by James B. Slaughter (available at the Essex County Museum and Historical Society)

2. Essex County Historical Society Bulletin. The Formation of Essex County. May 1972

3. Essex County Virginia: Historic Homes, 2002. by Anita and Gordon Harrower and Robert LaFollette (available at the Essex County Museum and Historical Society)

1729: Permanent Courthouse Established

The Essex County of 1692 included lands that comprise parts of modern Caroline, Spotsylvania and further west. Before his removal from office, Governor Spotswood secured the creation of Spotsylvania County (1721) that included northwestern portions of Essex.

The growing population of the remaining northwestern Essex, modern Caroline County, argued for a new county due to the difficulties of travel to the courthouse. People in lower Essex contested the loss of land because it would raise taxes. The courthouse was moved in the early 1700s to Lloyds in upper Essex to alleviate the feud.

With the creation of Spotsylvania, the courthouse moved back to Tappahannock. When the courthouse burned in the early 1720’s the feud between upper and lower Essex reached a climax. The General Assembly intervened; decided the Essex courthouse would be in Tappahannock; and created the new county of Caroline on 30 March 1728 from parts of Essex, King William and King and Queen.

The borders of Essex have remained basically the same since that time. A year later, Essex had built a courthouse on the public square that served until 1848. The same building was later used by Beale Baptist Church for a century. When Beale moved in 2007, the county purchased the building for additional office space and community use.

Sources:

1. Settlers, Southerners and Americans: The History of Essex County, Va.. 1985. by James B. Slaughter (available at the Essex County Museum and Historical Society

1766: Stamp Act Crisis

Some of America’s earliest organized resistance to British authority by patriotic groups like the Sons of Liberty took place in Essex in 1766.

Victory in the French and Indian War left England with vast new territory west of the Appalachian Mountains, but tremendous war debt and increased administration burdens. This led to a series imposed taxes on the American colonies by the British Parliament and the colonies rallying cry of “No Taxation without Representation”. In 1765, Patrick Henry was leading Virginia’s debate against England’s Stamp Act. He stated in the House of Burgesses, “that the general assembly of this Colony have the only and sole exclusive right and power to lay taxes and impositions on the inhabitants of this Colony”. Most of Virginia united in a boycott of the hated act, with Essex and the Northern Neck vigorously upholding the boycott. Some saw the financial benefits of cooperating with the act, including Archibald Ritchie, a wealthy Scottish merchant in Tappahannock. He openly declared his intent to comply with the law at the Richmond County Court.

Local patriots knew this could weaken resistance to the act, so they decided to act. Men from both sides of the Rappahannock River gathered at Brays Church in Leedstown, Westmoreland on February 27th 1766 led by Thomas Ludwell Lee and Richard Henry Lee of Westmoreland and Col. Francis Waring and and Col. William Roane of Essex. The first result was the drafting of six resolutions stating allegiance to England but publicly stating their grievances with the Crown. This was one of the earliest such documents in America and is known as the Leedstown Resolutions. The second result was action. Four hundred of the men, calling themselves the Sons of Liberty, gathered in Tappahannock on February 28 and compelled Ritchie to sign a public apology for his stance on the Stamp Act. This action by a group calling themselves the Sons of Liberty was seven years before the Boston Tea Party for which popular literature associates with the patriotic group. Virginia’s boycott held and England repelled the act. More importantly, Essex and Northern Neck leaders had gained experience in organization and action that would be well used in the coming years.

Archibald Ritchie would later become a staunch patriot and a member of the Association of Essex, a staunch boycott of all trade with England after 1774. His descendents would become local and state leaders in the coming decades and beyond. Ritchie’s beautifully restored home stands proudly today on Prince Street in Tappahannock.

Sources:

1. Settlers, Southerners and Americans: The History of Essex County, Va.. 1985. by James B. Slaughter (available at the Essex County Museum and Historical Society)

2. Essex County Historical Society Bulletin, Volume 8. Tappahannock and the Stamp Act (February, 1766), by Charles W. H. Warner. May 1975

3. Essex County Virginia: Historic Homes, 2002. by Anita and Gordon Harrower and Robert LaFollette (available at the Essex County Museum and Historical Society)

1776-1789 Goodrich Raids, Essex Resolutions, Meriwether Smith

With the repealing of the Stamp Act in 1766, tensions between England and the American Colonies eased for a short time. England’s authority over the colonies would soon be tested again by the Declaratory Act (1766), Townshend Act (1767), Revenue Act (1767), Tea Act (1773) and Coercive Acts (1774). In Virginia, the House of Burgesses was temporarily dissolved in 1769 and again in 1774 by the Royal Governor for resistance to British authority. By 1774, Virginians began to show signs of autonomy including joint declarations and successful non-importation pacts; active patriotic groups like the Sons of Liberty; and organized meetings of representatives at the Raleigh Tavern after the dissolving of the House of Burgesses. By the summer of 1774, citizens of Essex County were ready for action.

Veteran politician John Upshaw presided over a meeting of Essex citizens on 9 July to decide Essex’ position on relations with England. What resulted was a brave but loyal declaration of rights of Virginians as British citizens. 17 resolutions were established that first of all pledged allegiance to the crown; stated the power to tax and judge could only be exercised by elected representatives from Virginia; expressed support for the people of Boston; and initiated a non-importation pact on England goods. These Essex Resolutions and the earlier Leedstown Resolution represent two of the finest local revolutionary documents of their time.

By the summer of 1775, British rule in Virginia was unraveling. In June, Governor Dunmore ordered Royal Marines to remove gunpowder from the state magazine in Williamsburg. An angry group of patriots forced him from office and he retreated with his forces and loyalists to Norfolk. Battles with Virginia forces at Kemp’s Landing and Great Bridge in December forced Dunmore onto British warships. Dunmore’s fleet then commenced a campaign of plunder and destruction on Tidewater plantations. One of Dunmore’s loyalist supporters, Bartlett Goodrich, decided to try his luck on the Rappahannock River in April of 1776. Goodrich captured a vessel of corn offshore of Tappahannock without any resistance. Local militia from surrounding counties was now alerted, however, and they caught up with Goodrich several miles down river recovering the vessel and forcing Goodrich to flee. Men from Essex and Middlesex formed the 4th Company of the 7th Virginia Regiment and joined Washington’s army in January of 1777.

Essex County also made notable contributions on the political front. Meriwether Smith. Smith was elected to represent Essex at the Virginia Convention of 1776 to determine the question of independence from England. Smith represented conservative Tidewater gentlemen with a proposal that dissolved current relations but did not fully declare independence. Edmund Pendleton, chairman of the convention, used much of Smith’s proposal but called for united colonies free and independent states in the statement that was adopted. Smith was again called on to help George Mason draft the Virginia Declaration of Rights that would later form much of the Bill of Rights in the United States Constitution. Smith went on to serve in the Continental Congress in 1778 – 1780.

Sources:

1. Settlers, Southerners and Americans: The History of Essex County, Va.. 1985. by James B. Slaughter (available at the Essex County Museum and Historical Society)

2. Essex County Historical Society Bulletin, Volume 21. Col. Meriwether Smith and His Time, 1730-1794, by Emory Carlton. November 1982

3. Essex County Historical Society Bulletin, Volume 9. Essex Resolutions, July 1774 Exemplifies Revolution, by Charles W. H. Warner. November 1975.

1814: Essex Occupied by the British

After the revolution, Essex settled down to raising their families and crops in peace, while some ventured west in search of new land or a chance to make their fortune. War between England and France would soon begin to complicate their lives.

Naval competition between England and France began to impact American shipping due to international trade, the search for deserting seamen and the forced impressments of sailors for naval service. This led to violence on June 22, 1807. The British ship Leopard attacked the American frigate Chesapeake under the command of Captain James Barron, later to become a resident of upper Essex County. Three Americans were killed and 18 wounded in the British search for deserters. Essex, like the rest of Virginia, was furious about the attack. A county meeting resulted in public resolutions adamantly condemning the attack but not calling for war. The meeting was chaired by Colonel William Waring and attended by familiar Essex names such as James Garnett, Archibald Ritchie, Thomas and Newman Brockenbrough, Taliaferro Hunter and Sthreshley Reynolds. Essex natives in Richmond like Thomas Ritchie, Spencer Roane and John Brockenbrough led much larger rallies to condemn the attack.

Naval, political, trade and other tensions with England continued to increase until war was declared by America on June 18, 1812. The experienced and powerful British Navy effectively isolated the Chesapeake Bay, including the Rappahannock River. Dispersed militia units on foot could do little to oppose mobile British Marines supported by concentrated, shipboard artillery. Families along the Rappahannock waited with anxiety as British units attacked plantations, Urbanna and Hampton in 1813. Fear increased as the British strengthened their forces at Tangier Island under the command of Admiral Cockburn and burned Washington in August 1814. The British sword would soon be turned on Tappahannock.

On November 30 1814, a force of eight schooners along with thirteen troop and supply ships were sighted off Middlessex. The heavily outnumbered Essex Militia with one cannon was no match for this force and a short naval barrage of the town left no doubt about who had the upper hand. During their three days of occupation, nearly all the homes were pillaged and even some Ritchie family graves were desecrated. Thomas Ritchie was a well-known critic of England in his role as editor of the Richmond Enquirer. Afterwards, the British force continued to strike individual plantations along both sides of the Rappahannock.

Local militia, however, effectively ambushed a detachment of British at Jones’ Point and learned from deserters that Urbanna was the next target. Brigadier General John Cocke ordered all militia units in the area to Urbanna. The sizeable show of force deterred the British and the Rappahannock remained safe for the remainder of the war.

1. Settlers, Southerners and Americans: The History of Essex County, Va.. 1985. by James B. Slaughter (available at the Essex County Museum and Historical Society)

1817: James Mercer Garnett

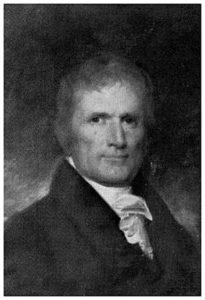

Of all the Essex County natives’ contributions to the state and nation, few if any have had more lasting impact than James Mercer Garnett. Born at Mount Pleasant in 1770, he was brother to Robert Selden Garnett Sr. of Champlain, also a state delegate (1816-1817) and congressman (1817-1827). James served in the Virginia House of Delegates (1800-1801) and two terms in the U.S. House of Representatives (1805 – 1809).

Garnett’s greatest contributions, however, were in farming and education. He strongly supported the improvement of farming knowledge, techniques and practices for all planters. Garnett knew that few Virginians would actively follow and implement the scientific farming literature of the age on their own. Instead, he favored the establishment of organizations to educate planters in a relaxed and often social atmosphere. To this end, Garnett helped establish the Fredericksburg Agricultural Fair, one of the earliest and longest running in America. He was elected its first president and served for 20 years. Encouraging a relaxed and competitive environment, Garnett helped establish agricultural fair traditions such as food and sewing competitions, tractor pulls and shooting contests. Garnett advocated establishing the Virginia Board of Education and became its first president. And finally, at the national level, he was elected the first president of the U.S. Agricultural Society in 1841 at the age of seventy-one. The Essex Agricultural Society and the strong farming tradition in Essex can thank James Mercer Garnett for much of their inspiration.

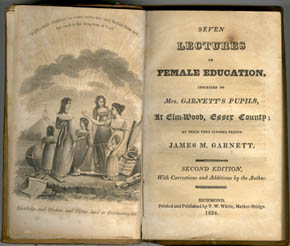

In addition to his agricultural interests, Garnett had progressive views on women’s education. Contrary to opinions of that time, Garnett felt that women had just as much right and capacity for intellectual development as men. Mary Mercer Garnett, James’ wife, operated the Elmwood Girl’s School at their home. He also published their progressive views in his 1824 book, Seven Lectures on Female Education. .

1820-1830: Essex County Antebellum Leaders

Essex natives significantly influenced America in the early 1800s by their shaping of Virginia politics and business. This series of lawyers, politicians and businessmen, sometimes called the Essex Junta, filled Richmond’s most prominent seats. While James Garnett was progressing agricultural methods and women’s education, the Junta was leading Virginia and influencing the nation during this formative period.

A variety of names can be associated with the Junta, but the most influential were Spencer Roane, Thomas Ritchie, and John Brockenbrough. Spencer Roane was appointed to the Virginia Court of Appeals, at 32 years old the youngest ever. He firmly defended the Bill of Rights, including religious freedom and the right to free slaves. His most famous and public battles were against Supreme Court Justice John Marshall on the roles of states and federal government. Due to an act of kindness to a stranger, a new county in western Virginia (now West Virginia) was named Roane and its county seat named Spencer.

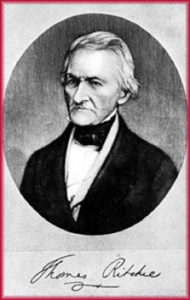

Thomas Ritchie, pictured here, was the editor and primary writer of the Richmond Enquirer from 1804 – 1845. The paper was the most popular in Virginia throughout this period. Thomas Jefferson encouraged the establishment of the paper and said, ” “I read but a single newspaper, Ritchie’s Enquirer, the best that is published or ever has been published in America.” Ritchie supported extensive internal improvements to Virginia, public schools and gradual emancipation of slaves. In 1845, President Polk helped to bring Ritchie to Washington to edit the newspaper The Union from 1845-1851.

Dr. John Brockenbrough, along with Ritchie, established Virginia’s first bank, Bank of Virginia, and helped to shape financial policies and business develpment throughout the state. His beautiful Richmond home would later become the White House of the Confederacy and is currently maintained by the Museum of the Confederacy. Other Junta members included George Smith, elected Governor in 1811 before tragically dying in the Richmond Theater Fire. William Brockenbrough and Francis Brooke also joined Spencer Roane on the Court of Appeals. Later in the Antebellum Period, R.M.T. Hunter and M.R.H. Garnett played critical national roles in the Civil War era.

Virginians filled the White House continuously for most of the 1800s first quarter. Virginia was one of the largest, most populated and wealthiest states during that time. By their dominant role in state affairs and connections to national leaders, the Junta significantly influenced America during this formative period.

Sources:

1. Settlers, Southerners and Americans: The History of Essex County, Va.. 1985. by James B. Slaughter (available at the Essex County Museum and Historical Society)

2. Essex County Virginia: Historic Homes, 2002. by Anita and Gordon Harrower and Robert LaFollette (available at the Essex County Museum and Historical Society)

3. Essex County Historical Society Bulletin, Volume 5. The Significance of the Richmond Junta (Essex Junta), by Anne Frost Waring. November 1973

4. Essex County Historical Society Bulletin, Volume 26. Virginia Governors from Essex County, by E. Lee Shepard. May 1985

1834-1865: R.M.T. Hunter

Robert Mercer Taliaferro Hunter, a big name comparable to his place in history. R.M.T. Hunter became the most famous of all Essex statesmen, serving his county, state and country during the troubled Civil War Era.

Hunter grew up part of the Garnett political tradition, studied law at the University of Virginia and began his practice around 1832 in Lloyds, near Champlain. He progressed from the House of Delegates (1834) to the House of Representatives (1837) and then to the Senate (1847). Hunter was often a moderate between Whigs and Democrats and was a supporter of the States Rights Doctrine. His “independent” position helped him be selected Speaker of the House (1839) at the age of 30, the youngest ever, but sometimes cost him elections that core party affiliation helped provide. He also tended to rely on his character and reputation for elections, rather than active campaigning techniques.

Hunter’s moderate position continued as the crisis between South and North grew. He was an “acceptable Southerner” to Northern papers and even made a bid for the Presidency in the tumultuous 1860 election. When Southern Democrats walked out of their second successive National Convention, Hunter showed his ultimate allegiance to Virginia and joined them. No compromise would succeed and he wrote, “you may place your little hand against Niagra Falls with more certainty of staying the torrent, than you can oppose this movement”. Despite his recognition of the inevitable, Hunter continued his efforts toward peace and even mediated between Confederate and Union representatives before Virginia seceded. After Virginia joined the Confederacy, Hunter whole-heartedly played a leading role in its government.

Active at once, Hunter initiated the decision to move the capitol to Richmond and was soon appointed Secretary of State. He sought to use “King Cotton” as leverage with European nations to gain their aid to break the Union blockade of Southern ports. His image even appears on the Confederate $10 bill. He soon found he didn’t like working for the President’s Cabinet and instead enjoyed the freedom of a Confederate Senate position (1862). There he stayed for the remainder of that desperate conflict.

As the end and defeat loomed, Hunter helped lead a peace delegation (January 1865) to Lincoln. It was far too late though; only “Unconditional Surrender” would appease the North. So, he went home to Fonthill and his wife “Line”, was taken prisoner while having dinner at Epping Forest and sent to Fort Pulaski, Georgia until the following fall.

Coming home at last, R.M.T. Hunter confronted the reality of poverty and debt. The institution of slavery was thankfully gone forever and Essex would slowly learn to cope in this new world. Throughout the challenging Reconstruction Period, Hunter continued a life of public service first as State Treasurer and finally the modest post of Custom’s Collector for the Port of Tappahannock. The county’s most famous politician died in 1887 at the age of seventy-eight and is buried at Elmwood.

Sources:

1. Settlers, Southerners and Americans: The History of Essex County, Va.. 1985. by James B. Slaughter (available at the Essex County Museum and Historical Society)

2. Essex County Virginia: Historic Homes, 2002. by Anita and Gordon Harrower and Robert LaFollette (available at the Essex County Museum and Historical Society)

3. Essex County Historical Society Bulletin, Volume 15, Portrait of a Virginia Statesman, Dr. John E. Fisher. May 1979

1861-1865: The 55th Infantry & The 9th Cavalry

Essex, like most Virginia counties, had a long tradition of volunteer militia. “Mustering Days” were a highlight of the year. The decline of the militias through much of the 1800s was changed by the John Brown Raid of October 1859. By March of 1860 the Essex Sharpshooters had formed as a volunteer unit with about 100 men. They could have no idea of the challenges they would meet in the next five years.

After Virginia seceded, units rapidly formed to prepare for her defense. Essex fully committed and nearly every able-bodied, white male served. Local units were initially organized as “Major Ward’s Essex and Middlesex Battalion” under the command of Major William N. Ward, a local teacher and Episcopal minister. Eight of these original nine companies would form the nucleus of the 55th Virginia Infantry; their cavalry would be attached to the 9th Virginia Cavalry. Major Ward’s core companies were the following:

– Company A, Essex Artillery, enlisted May 21st 1861 under Captain Evan Rice

– Company B, Middlesex Artillery, May 24th 1861, Captain William Fleet

– Company C, Middlesex Southerners, May 24th 1861, Captain Andrew Saunders

– Company D, Essex Davis Rifles, June 17th 1861, Captain Gustavus Garnett Roy

– Company E, Westmoreland Greys, June 24th 1861, Captain J. Bailey Jett

– Company F, Essex Sharpshooters, May 21st 1861, Captain Thomas Burke

– Company G, Essex Grays, June 12th 1861, Captain George Street

– Company H, Middlesex Rifles

– Four companies would be added later from Essex, Middlesex, Lancaster and Fredericksburg

The 55th with the toil of 300 slaves and free African-Americans built Fort Lowry and maintained the defense of the lower Rappahannock from there and its satellite units: Camps Byron, Sullivan, Field and smaller camps in Middlesex. The regiment joined Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia and saw its first real action during the Peninsula Campaign in June of 1862. The men of the 55th stayed with Lee through almost all the major battles in Virginia, Maryland and Pennsylvania. Please see the sources below for a full accounting of the bravery and sacrifice of these men. The dedication on the Confederate monument on Prince Street in Tappahannock reads as follows, ” They fought for the principles of State Sovereignty and in defense of their homes.”

Virginia counties also formed individual cavalry units soon after Virginia’s secession. The Essex Light Dragoons were assigned cavalry duties in support of Fort Lowry. Special orders on December 18th 1861 established the 9th Virginia Cavalry under the command of Col. John E. Johnson. The original companies consisted of the following:

– Company A, Stafford Rangers, established May 6th 1861

– Company B, Caroline Light Dragoons, May 6th 1861

– Company C, Lee’s Light Horse (Westmoreland), May 25th 1861

– Company D, Lancaster Cavalry, April 25th 1861

– Company E, Mercer Calvary (Spotsylvania), April 25th 1861

– Company F, Essex Light Dragoons, June 10th 1861

– Company G, Lunenburg Light Dragoons, June 7th 1861

– Company H, Lee’s Rangers (King William), June 10th 1861

– Company I, Potomac Cavalry (King George), October 12th 1861

– Company K, Richmond County Cavalry, October 24th 1861

Of the 309 known professions in the regiment, 164 were farmers, 33 doctors, 33 students, 12 lawyers, 12 clerks, 11 mechanics and 10 teachers. The average age was about 26. The 9th Cavalry would be attached to General “JEB” Stuart throughout the war and was continuously engaged in major and minor actions in Virginia, Maryland and Pennsylvania. A lasting tribute was paid to the 9th Cavalry by their Federal Cavalry foe H.J. Kilpatrick who wrote that when he knew the 9th was in the front he always put three regiments to fight it because they were the best cavalry regiment in the Confederate service. 37% of the men in the 9th would be killed, wounded or captured but they would remain a strong and active unit until Appomattox. For a full description of their bravery and sacrifice, see the sources below.

Sources:

1. Settlers, Southerners and Americans: The History of Essex County, Va.. 1985, by James B. Slaughter (available at the Essex County Museum and Historical Society)

2. Essex County Historical Society Bulletin, vol. 19. Tappahannock and Its Role in the War Between the States, by Carrol M. Garnett. November 1981

3. 55th Virginia Infantry, 1989. by: Richard O’Sullivan

4. 9th Virginia Cavalry, 1982. by: Robert K. Krick

1861-1865: General Robert S. Garnett & General Richard B. Garnett

Major Robert Selden Garnett Jr. was born on December 16, 1819 and raised at his father’s home, Champlain, in upper Essex. A tradition of civilian and military distinction surrounded him. Robert Selden Garnett, Sr., his father, studied law at the College of New Jersey (later Princeton), served one term in the Virginia House of Delegates and five terms (1817-1827) in the U.S. House of Representatives. His uncle, James Mercer Garnett, also served in the House of Representatives, and was a leading agriculturalist and advocate for women’s education. His mother, Olympia Charlotte de Goughes, was the daughter of a French general and a leading French feminist. His cousin of nearly the same age, Richard Brooke Garnett who lived at nearby Rose Hill, also experienced a tragic death, but later in the war at Cemetery Ridge in Gettysburg. It is easy to imagine the two as youths riding without a care through the fields and forests of Occupacia before their years of service. Robert and Richard would later attend West Point together, graduating numbers 27 and 29 respectively in the Class of 1841. Their classmates would later be generals on both sides of the battle line, including Confederates: Josiah Gorgas, Samuel Jones, Claudius Sears, Abraham Buford, and Federals: Zealous Tower, Horatio Wright, Albion Howe, and Alfred Sully.

Robert S. Garnett, Jr. saw action in the war with Mexico. He ended up serving as an aide-de-camp for General Zachary Taylor, participating in the important battles of Palo Alto, Resaca de la Palma, Monterey, and Buena Vista, rising to the rank of First Lieutenant in 1846. After the war he became a captain in the infantry, leading expeditions against the Yakima Indians and participating in the military administration of California. He later served as Commandant of Cadets at West Point (1852-54) while Robert E. Lee was Superintendent. He was promoted to Major in 1855. At the outbreak of the Civil War, Garnett resigned his commission in the U.S. Army to fight for his native state. He was commissioned a Brigadier General in the Confederate Army on June 6, 1861 and assigned the defense of northwest Virginia (now the state of West Virginia). Despite valiant efforts, his vastly outnumbered command was forced into a retreat. On July 13, 1861 he led a small detachment to Carrick’s Ford on the Cheat River to stall the advance of Federal troops while the bulk of his force escaped. He was killed while bravely leading his men, becoming the first general to be killed in the war. His former West Point roommate, Major John Love, was the first Union officer to come to his side.

Richard Brooke Garnett began his career serving in the Second Seminole War in Florida, and then served throughout Missouri, the Indian Territory, Arkansas, Texas and South Dakota. He also served with General Albert Sydney Johnston in the Utah Expedition of 1857-58. When news of Virginia’s secession reached him, he resigned from the U.S. Army on 17 May 1861 and offered his sword to his native state. By fall of that year, he was Lt. Colonel second in command of Col. Thomas R.R. Cobb’s famous Georgia Legion. By spring of 1862, he was promoted to Brigadier General in command of the even more famous Stonewall Brigade.

In March of 1862, a battle of Stonewall Jackson’s famous Shenandoah Campaign was fought at Kernstown, VA. It would be a disaster for Richard Garnett though. Due to incorrect intelligence, the Stonewall Brigade was sent against a vastly superior federal force. After two hours, fighting on three sides and low on ammunition, Garnett ordered the Stonewall Brigade to retreat. A furious Jackson relieved Garnett from command and had him arrested pending court-martial. The court-martial was never convened due to the demands of campaigning. Garnett never had the opportunity to clear his name, and most historians support his position. After Jackson’s death, Richard was one of his mourners and reportedly said to Major Sandie Pendleton and Captain Kyd Douglas: “You know of the unfortunate breach between General Jackson and myself. I can never forget it, nor cease to regret it. But I wish here to assure you that no man can lament his death more sincerely than I do. I believe he did me a great injustice, but I believe also he acted from the purest of motives. He is dead. Who can fill his place!”

At Gettysburg, General Richard B. Garnett was a brigade commander in Pickett’s Division. When that desperate charge was made on Cemetery Ridge, an ailing Garnett led his men from the saddle knowing his probable fate. He bravely led his troops almost to the federal lines before being struck down. A marker in Richmond’s Hollywood Cemetery commemorates his courage and sacrifice. He was later awarded the Confederate Medal of Honor by the Sons of the Confederacy.

Sources:

1. Settlers, Southerners and Americans: The History of Essex County, Va.. 1985, by James B. Slaughter (available at the Essex County Museum and Historical Society)

2. Essex County Virginia: Historic Homes, 2002. by Anita and Gordon Harrower and Robert LaFollette (available at the Essex County Museum and Historical Society)

3. Essex County Historical Society Bulletin, vol. 50. Major Garnett and the California State Seal. by Robert LaFollette. March 2008

4. Essex County Historical Society Bulletin, vol. 27. History of the Confederate Medal of Honor and of Richard Brooke Garnett, Brigadier General, C.S.A., an Essex Native. by Col. Joseph B. Mitchell, USA (Ret.) . November 1985

1861-1865: Essex County Occupied by the Federal Forces

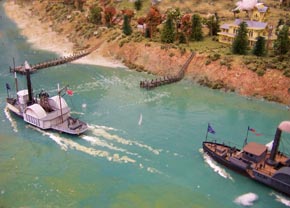

The Essex home-front was not immune to the violence in the War of 1812; it suffered much more in the Civil War. Once Fort Lowry was abandoned, the Rappahannock Valley was vulnerable. The river would serve as an increasingly open highway for Federal gunboats to patrol, raid, shell and loot. Many Essex family homes, wharfs, mills, crops and barns suffered; their stories have passed down through the generations.

One of the first documented attacks came in April 1862 by a flotilla of gunboats called the “Rappahannock Expedition” under the command of Lt. E.P. McCrea. The expedition attacked the abandoned Ft. Lowry and continued upstream igniting terror in Tappahannock. They occupied town and made Dr. Roane’s home (later the Trible House and the Essex Inn) their headquarters. A romantic story emerged that Essex Dragoon Philip Lewis snuck into town that night to gather intelligence. Upon discovery he was ordered to halt, after which he turned in his saddle, waved and said, “No halt in me, gentleman” and rode off.

The most traumatic gunboat attack on Essex happened in June of 1864 by Colonel Alonzo Draper. Four gunboats, transport vessels and 500 African-American troops of the 36th Regiment made the infamous Draper Raid. Their destructive mission stole livestock and machinery, destroyed civilian boats and burned the mill of Senator R.M.T. Hunter. Judith Brockenbrough McGuire vividly details the chaos and damage in her diary (see below). The losses in combination with two years of war and blockade were devastating to Essex. The Draper Raid did, however, bring freedom to many African-Americans who had experienced many more years of slavery.

A war weary Tappahannock suffered its last reported attack on 13 March 1865. A Federal side-wheel steamer with three cannon and 57 sailors attacked the town, destroying the boats, the ferry and the Gordon’s Creek (probably Hoskins Creek) Bridge. As the Federals moved down river, Confederate artillery at Paradise Plantation was able to send a final few shots at the intruders.

Sources:

1. Settlers, Southerners and Americans: The History of Essex County, Va.. 1985, by James B. Slaughter (available at the Essex County Museum and Historical Society)

2. Essex County Historical Society Bulletin, vol. 19. Tappahannock and Its Role in the War Between the States, by Carrol M. Garnett. November 1981

3. Diary of a Southern Refugee during the War, by a Lady of Virginia, 1889. by Judith Brockenbrough McGuire

1861-1865: The Burial of Latane

By June of 1862, Union General George McClellan had driven his enormous army to the outskirts of Richmond. He was confident the Confederate capitol would fall and the war would soon be over. Spirits in Richmond and the Confederate army were low. On June 12th, General Robert E. Lee sent Virginia’s own General “JEB” Stuart on a scouting mission with 1200 of his cavalry. This mission would develop into Stuart’s famous “Ride Around McClellan” which enthralled the Confederacy and perplexed McClellan.

The Essex Light Dragoons of the 9th Virginia Cavalry led the column in the area of Hanover Courthouse. The mission encountered resistance from a federal cavalry unit so the dragoons attacked with their Captain William Latane M.D. leading the charge. The federals were driven off, but Captain Latane was killed. His death would be the only one among Stuart’s dragoons during this famous maneuver.

John Latane stayed behind to care for his brother’s body as the column continued. John sought assistance from the nearby Westwood plantation. He left his dear brother’s burial to the ladies’ care only after their assurance “to bury him as kindly as if he were a brother”. No minister could be found, so the ladies, children and slaves of Westwood and Summer Hill Plantations buried him at Summer Hill as Stuart was riding triumphantly into Richmond. A modest headstone marks his grave. Latane’s quiet and simple burial would not soon be forgotten though.

Soon afterwards, John R. Thompson wrote a poem commemorating and romanticizing Latane’s death and burial. The poem in turn inspired an oil painting in 1864 by William D. Washington. In the late 1800s, both the poem and the painting became major icons of the “Lost Cause”. Many families honoring the courage of Virginia and the South displayed the Burial of Latane on their mantel throughout the 20th century and even today.

Sources:

1. Settlers, Southerners and Americans: The History of Essex County, Va.. 1985, by James B. Slaughter (available at the Essex County Museum and Historical Society)

2. Essex County Historical Society Bulletin, vol. 53. The Propaganda of Martrydom: The Latanes and Confederate Nationalism. by Ryan Danker. September 2009

1880-1920: The Steamboat Era

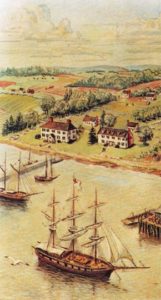

From Virginia’s earliest colonial days, creeks and rivers served as highways for commerce and transportation. Wharfs along Essex shores saw tobacco and other agricultural products exported and manufactured goods imported from around the world. These wharfs became local hubs for business and the accompanying social activity. General stores, post offices, hotels, canneries and ferries often complemented the wharf. For the sleepy towns along Virginia’s tidal rivers, wharfs were a focus of daily life and the community came to life with the docking of each steamboat.

After the Civil War, Virginia’s economy was devastated and steamboats served as a vital economic link for struggling Essex. Several times a week, steamboats headed upriver stopping at Bowler’s Wharf, Ware’s Wharf, Tappahannock, Blandfield, Layton’s Landing and Saunder’s Wharf before returning to Baltimore. The steamboats took on cargo from local farms, mills, canneries and waterman, but they also carried passengers. An exciting steamboat trip could last a few short hours along the river or several days in an elegant stateroom. Many honeymooners would begin their married lives with a trip aboard ships like the Rappahannock, Lancaster, Middlesex, Wenonah, Westmoreland and Anne Arundel. A special highlight along the river was the arrival of the Adam’s Floating Theater. A usually packed house of 700 seats paid 35 cents to see a professional cast of New York actors and musicians.

Steamboat operations changed names and hands several times over the years. Companies like The Baltimore and Rappahannock Steam Packet Company (1830) and Weems Line (1875) wrote their names in the lore and romance of the steamboats. Changes came slowly but steadily as automobiles and increased railways changed the patterns and pace of transportation. New bridges like the Downing Bridge (1927) at Tappahannock also impacted the steamboats and the wharfs they served. By the 1930s, steamboat use was in decline and a terrible storm in 1933 destroyed many of the remaining wharfs. When the Anne Arundel left Saunder’s Wharf for the last time on April 11, 1937 a beautiful page of life on the Rappahannock had been turned. Saunder’s Wharf, stop Number 27 on the Weems Line (photo below), stands today as one of the last remaining steamboat wharfs on the Chesapeake Bay.

Sources:

1. Settlers, Southerners and Americans: The History of Essex County, Va. by James B. Slaughter. Walsworth Publishing Co., Inc., 1985. (available at the Essex County Museum and Historical Society)

2. Essex County Historical Society Bulletin, Volume 49. The Wares of Ware’s Wharf, by Carol Garnett. March 2007

3. Essex County Virginia: Historic Homes, 2002. by Anita and Gordon Harrower and Robert LaFollette (available at the Essex County Museum and Historical Society)

4. Steamboats Out of Baltimore. by Robert H. Burgess and H. Graham Wood. Tidewater Publishers, 1968.

1920: Modern Essex